Born into a Jewish ghetto in the Russian Empire of Lithuania in 1869, Emma Goldman grew up to become one of history’s best-known anarchists and fiercest feminist voices, with her work earning her admiration from many working people, and hostility from those in power…

An ‘energetic political organiser, a fiery radical, and a passionate free spirit’, Goldman was attracted to anarchism as a philosophy, not only because it sought economic and political justice, but also because anarchists advocated free speech, sexual freedom, and atheism (despite being Jewish, Goldman saw religion as a form of oppression).

She wrote copiously on capitalism, labor, marriage, birth control, sexual freedom (for people of all sexual orientations)*, prisons, war, art, and freedom of speech.

*Never one to shy away from disapproval of the mainstream, Goldman was one of the first outspoken allies of gay and lesbian people anywhere in the world. Firmly believing that ‘the most vital right is the right to love and be loved.’

Because of her supposedly ‘radical’ views, and steadfast determination to make those views heard, her speeches and writings on workers’ rights, revolution, women’s oppression, and religion, struck fear into the powers of the state and capital… So much so that FBI director J. Edgar Hoover dubbed her as “the most dangerous woman in America.”

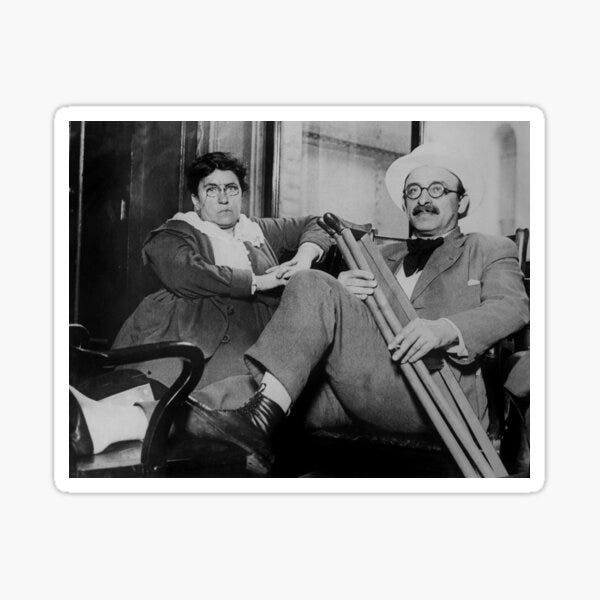

1889, aged 20, saw Goldman emigrate to join her sister in New York City where she became involved with a series of ‘Jewish radicals.’ It was in New York where she met Alexander Berkman, a fellow Lithuanian anarchist who would become her lifelong comrade and longtime romantic partner.

However, in 1892, Berkman landed in prison following an assassination attempt on industrialist Henry Clay Frick during the Homestead steel strike (which Goldman helped him to plan, in an effort to bring about a revolutionary workers’ uprising). After a 14-year prison sentence, he was released.

Goldman too was arrested several times throughout her life, one such time being in 1893 after being (falsely) implicated in the assassination of President William McKinley by fellow anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, who claimed her as an inspiration following a speech.

If they do not give you work, demand bread. If they deny you both, take bread.

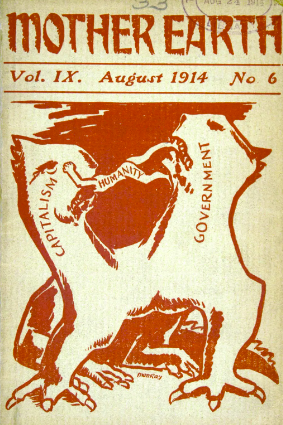

Following her release from prison in 1906, Goldman founded and edited ‘Mother Earth’, an influential anarchist journal.

A big proponent of free love, she also lectured on the concept of an ‘uncoerced attachment between two persons for whom conventions of law and church were irrelevant.’

Following her advocacy on these themes, she was jailed briefly (again) in 1916 [specifically for speaking out on birth control, which she deemed a ‘form of female slavery’].

And again, in 1917…

She was jailed again but, this time, a two-year sentence for speaking out against military conscription, and her opposition to the United States’ involvement in World War I…

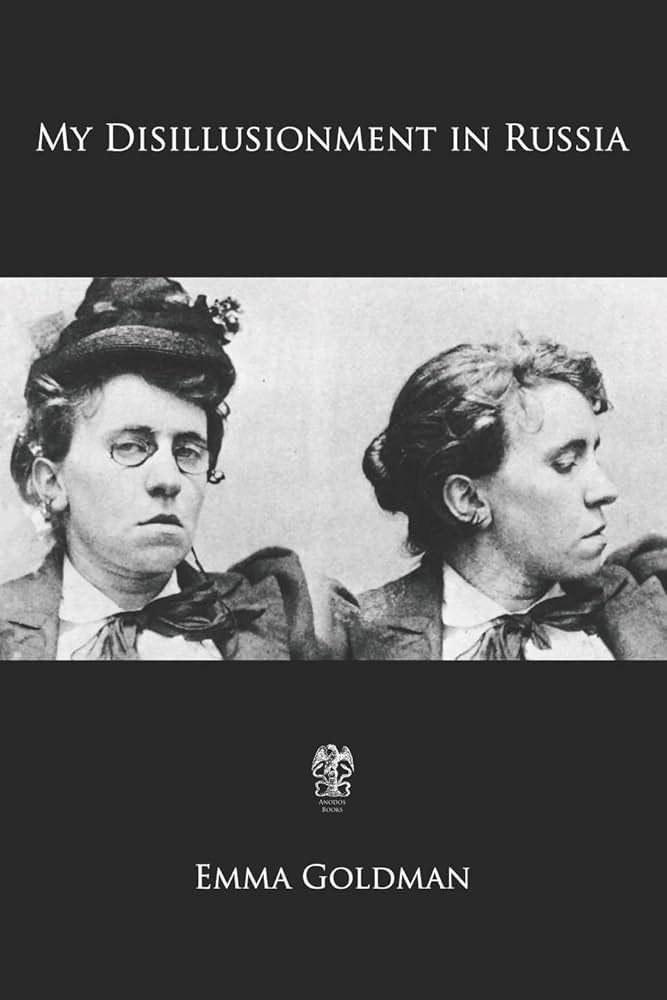

By the time of her release in September 1919, Goldman — “Red Emma,” as she was called — was declared a ‘subversive alien’ and in December, along with Berkman and 247 others, was deported to Russia. Goldman recounted her experiences, particularly on the political exile she faced, in her 1923 published book, ‘My Disillusionment in Russia.’

Goldman subsequently left Russia and traveled all around the world to continue her work in fighting for social justice, while continuing to lecture and write her autobiography, Living My Life (1931).

At the time of her death in 1940, aged 70, Goldman was living in Toronto, Canada, and working for the antifascist cause in the Spanish Civil War.

Even in the face of continuous retribution from authority, Goldman kept advocating for what she believed in right until the end, wavering the right to her own freedom to fight for the freedom of the masses:

(^ The true meaning of altruism).

Goldman is remembered as an earthy, bohemian woman who loved art, music, and sex, and saw no reason for a revolutionary to deprive themselves of beautiful things.

I want freedom, the right to self-expression, and everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things. Anarchism meant that to me, and I would live it in spite of the whole world — prisons, persecution, everything. Yes, even despite the condemnation of my own comrades I would live my beautiful ideal.

[Living My Life (New York: Knopf, 1934), p. 56]

Goldman’s life work:

To spread the message of liberation, far and wide.

As she wrote in a 1910 essay;

Anarchism is the great liberator of man from the phantoms that have held him captive.