Nowhere does ‘love means love’ ring truer than in Paris, the city of love and the capital of the first (modern) country to legalise same-sex relationships.

While homosexuality wasn’t decriminalised until 1967 in the UK, and even later still in the US (2003), in France, homosexuality was decriminalised approximately two centuries before, in 1791 at the end of the French revolution.

The Revolution of Love

With an amendment to the penal code, a ‘crowd of imaginary crimes’ including sodomy were abolished.

‘Private acts by private individuals are not a matter for state intervention’, the French authorities said, thus inspiring the first wave of the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Western Europe.

With its open mindedness triggered by the French Revolution, a time of political upheaval, from the late 18th century, Paris became the place to be for creatives. Queer writers in particular, including the likes of Oscar Wilde and James Baldwin no less, flocked in their droves to the French capital.

Not only did Paris provide queer people with a place where they could live openly, but it also provided everyone, no matter their sexual orientation, with a place where they were granted permission to just… exist.

Pursuing goals because, ‘#productivity’, too many of us, in the modern Western society within which we live, forget that the prerequisite to doing is being.

Idyllic for writers, with cafes on every corner, Paris however, with its slow way of living, reminds us of that, and they even have a word for it; ‘Flaneuring.’ The art of wandering around without intention or direction.

The Parisian life is good because in it, life can just be life. Slow and intentional.

Someone else who moved to Paris as the French Revolution drew to a close was the trailblazing American bookseller and publisher, Sylvia Beach.

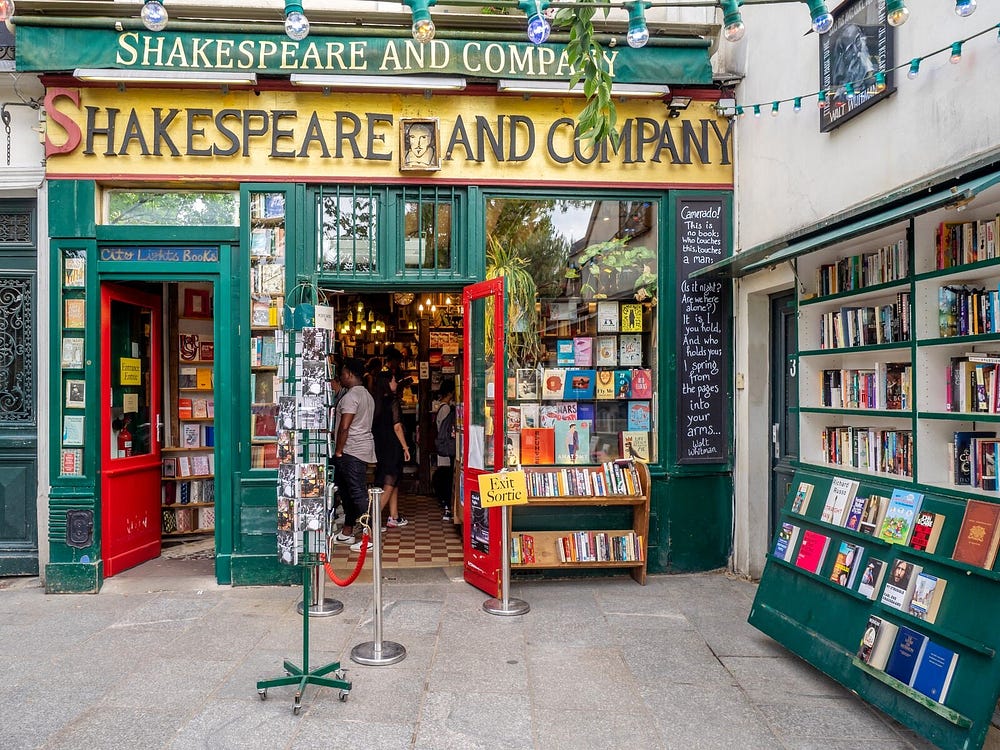

Beach exchanged the noise of America for the calm ease of Paris at the age of 30. Once there, she set up the independent bookshop, ‘Shakespeare and Company’, in 1919 with her partner, Adrienne Monnier.

A ‘sanctuary for progressive writers’ and a ‘hub for innovative publishing’, Shakespeare and Co was the first combined English-language bookshop in Paris. Also a ‘lending library’, it gave cash-strapped readers in post-World War I Paris unprecedented access to Anglo-American literature.

With an ethos very much centered on literature for literatures sake, Beach wasn’t in the business to make money as much as she was in it to make a difference.

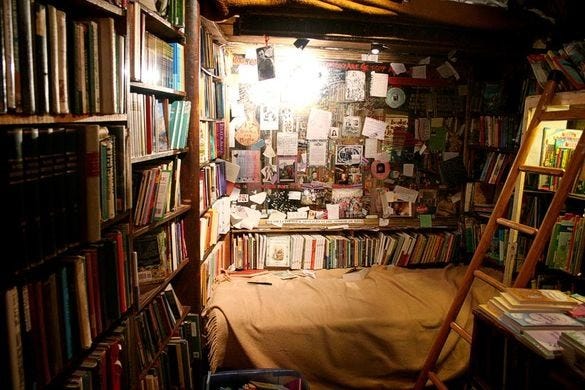

It’s why Beach would encourage visitors to browse and read books in her store for hours without making them feel under any obligation to buy. Or leave. Beach also regularly offered writers a bed for the night under a ‘tumbleweed’ scheme, something which many established writers and aspiring wordsmiths alike took her up on.

An estimated 30–40,000 people (and counting, it is still running today) have slept in Shakespeare and Co as part of the scheme…

As Edwina Hart, travel writer and former ‘tumbleweed’ wrote in this blog post:

My fellow “tumbles” were like characters from a novel; a mix of Oxbridge undergrads, artists, poets, and bohemians — united by a love of literature. After the shop opened at 9 am, we would meander the backstreets of the quarter and pause at a local tabac for an espresso served at the bar. Following in the footsteps of Hemingway, we frequented his old haunts and continued towards the “wonderful, narrow street market” of rue Mouffetard. Here we would use the jangling purse of coins donated in the bookstore wishing well (Sign: “Feed the starving writers”). We’d buy a baguette on rue Monge and, if the donations were generous that week, some gooey Camembert.

While the Tumbleweed scheme still exists today, it is in a different location, in a later ‘Shakespeare and Company’ that was set up by George Whitman.

Whitman opened what was originally called Le Mistral, dubbed by Slyvia Beach as the ‘spiritual successor’ to Shakespeare and Company in 1951. In 1964, two years after Sylvia’s death, Whitman changed the store’s name to Shakespeare and Company in Beach’s honour.

The store is, as of January 2025, run by George’s daughter, Sylvia (named after Sylvia Beach), and follows the same ethos now as it did then.

In trying to uphold Beach’s legacy, smaller publishes are prominently displayed on their shelves, with the aim to ‘offer a diversity of contemporary voices and subject matters’, the latter point being something that Beach, who helped shape the literary landscape of her age, prided herself on…

Shakespeare and Company (1919) was the first place of publication for some of the most important poets, novelists, and critics in the early decades of the 20th Century, including, most famously, Irish writer James Joyce who had been trying (unsuccessfully) to publish ‘Ulysses’ for several years.

After meeting Joyce in 1920 when nobody would publish his novel because it was deemed obscene, ‘far too hot to handle’, Beach decided that Shakespeare and Co. would put the book out, making it, for many years, the only place on the planet where you could get a copy.

‘It sounds to me like the ravings of a disordered mind — I can’t see why anyone would want to publish it.’

As a lesbian, Sylvia Beach knew all too well the tools that the people in power will use to stay in power.

The authorities hated Ulysses because they feared it. It’s why Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, the editors of the Little Review (1918) were summoned to court owing to them having ‘violated New York’s anti-obscenity law’ when they printed a mere excerpt of the book.

It’s also why, in 1931, the BBC prohibited its radio programmes from so much as even mentioning the title of Joyce’s novel on air.

In 1921, John Sumner, the man who led the Little Review prosecution, argued that “radical feminists” were “writing insidious books on the freedom of the modern woman, and advocating still greater sex freedom” (contraception, perhaps, or information about contraception, both of which were illegal). Censors like Sumner assumed that Ulysses’ characters would lead women down a path of ‘ever-expanding permission ending in broken families and a ruined nation.’

Reviewers saw Ulysses not just as obscene but as “completely anarchic”.

Exploring sexual pleasure outside marriage could lead to questions about the wisdom of marriage and monogamy itself, authorities feared, which opened the door to questioning all unexamined pieties, including nationalism, capitalism, and religion.

Alas, ‘If a man holds up a mirror to your nature and shows you that it needs washing, it is no use breaking the mirror. Go for soap and water.’

George Bernard Shaw.

Unafraid to stand for what was right, and fearless of the repercussions that might arise in doing so, we have Beach and her literary comrades of the twentieth century to thank for our freedom in the twenty-first.

Paris, and the modernism that it, in many ways, birthed, is the mirror, as held up by Sylvia Beach, and Margaret Anderson, and George Whitman, and Jane Heap, and all the other trailblazers of the twentieth century, through which we are all reflected.

Because of them, we don’t have to live in fear that one day we might produce the ‘wrong’ kind of art and end up in jail because of it. We don’t have our self-expression diluted, our words banned, our voices stifled.

Because of them, we can write about masturbation and sex and abortion, and secularisation and white supremacy and capitalism, all the things that were deemed too close to home, ‘off limits’, a century ago.

Because of them, we are free.