-

Power Corruption: The Epstein Files Unveiled

What is coming out in the Epstein files is a prime example of how power corrupts, and how the people responsible for such corruption will do whatever it takes to keep their power in place. This is why marginalised people are turned into scapegoats. It’s also why refusing to look the other way to prescribe to the lies of those in power sees people being labelled as ‘woke.’

Donald Trump once said that the Epstein files were merely fabricated by members of the Democratic Party. Now that we know how prevalent Trump is in the files, we can see why he said this.

“Epstein is a terrific guy who likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side”, Trump said in a 2002 interview with New York magazine.

We’re not ‘woke’, we’re awake.

We’re awake to the truth…

Making scapegoats out of the marginalised to cover their backs

There are no trans people in the Epstein files, or ‘illegal’ immigrants, the two minority groups that are most under target. What there is, however, and in abundance at that, is the world’s richest and most powerful. This includes high-profile figures in entertainment, and even more worryingly, government advisors, and, in America’s case, Presidents, both current (Donald Trump), and former (Bill Clinton). And the reason for this is simple. With money, the law (or rather, the lack thereof) can be bought.

This is why, despite having been accused of rape, sexual assault, and sexual harassment by at least 25 women, Donald Trump is the president of the most powerful country in the world.

When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything.

… Grab ‘em by the pussy.On multiple occasions, Trump has stated that if Ivanka were not his daughter, he might be dating her. This included a 2006 appearance on The View where he and Ivanka appeared together, and he remarked that she had a “very nice figure”.

If commenting on your own daughter’s sexuality wasn’t bad enough, in 2023, a New York jury found Trump liable for the rape of the American journalist and author, E. Jean Carroll. Trump was ordered to pay $83.3 million in damages as a result.

Just consider that for a moment, and let it sink in…

Let it sink in that the same man who is the current president of the United States is a rapist, and there’s proof.

Make it make sense…

The question is… Why?

It might not make sense why such people are allowed to be in charge of a whole country, but what does make sense is that none of it is about sex, it’s all about domination.

It’s one thing to want to dominate a country that hasn’t given consent (as Trump has proven, he’s hungry for it, just ask Greenland), but it’s quite another to want to dominate a body that hasn’t given consent. To make it yours. To silence it. Restrict it. End it, if you want.

Power-hungry people, evidently, will stop at nothing to get what they want, even if the cost of it is their own humanity.

-

The Role of Art in Anorexia Recovery

The whole effort of an anorexic is directed towards control of the uncontrollable: the body, other people, and ultimately, life and death.

So terrified are they of losing control that they are frozen on the borderline of life and death, power and madness.

Such a yearning for control, in most cases, originates in childhood, where children were either told that they should keep their feelings ‘firmly under wraps and not expressed at all’, or they were in the firing line of violent outbursts where people got hurt emotionally and/or physically. In either case, there was no room, for example, for anger or grief to come and go. This is why, in adolescence, the children of such families might develop anorexia.

The mind/body split

When eating becomes the primary focus of one’s life, demanding continual planning and self-discipline, the obsessive preoccupation serves as a defence against experiencing painful emotions. It therefore also acts as a preventative factor against the outbursts reminiscent of their childhood.

By separating the body from the mind, external perfection can be sought to compensate for profound feelings of inferiority. This is how anorexics can get to such low weights and keep going. It’s all driven by the distorted logic that their body, a ‘foreign container’, is filled with all the bad feelings, and that only once it is destroyed can their mind, the ‘real me’, be free of intolerable feelings, painful memories, and physical harm.

Anorexics have this perspective, given that the unhappy family situations that so many grew up in could not in any way provide a safe enough setting for them to experience a normal, full range of feelings and learn to survive them without disastrous consequences. So often, there were disastrous consequences to ordinary healthy feelings, whereby it was impossible to feel angry, for example, without also feeling guilty. And so, they learned to squash their emotions so as not to cause further distress.

No matter how emaciated I am, all is well. I don’t know what all the fuss is about.

For people with eating disorders, their self-worth only seems to exist if it is validated by an external source. This is why, when they eat ‘good’ food, they can allow themselves to feel ‘good’ as a person, until the time when they eat ‘bad’ food, and then the pattern reverses.

As well as relationships within the family being troubled for many people with eating disorders, another familial similarity can be seen in the particular roles that many anorexics played within their families when they were children.

Taking on the role of the ‘responsible child’ is a common experience in eating disorder patients. This often includes taking on what are generally considered parental tasks, for example, having considerable responsibility for the running of the home. Generally, these tasks hold a lot of responsibility, but ultimately, the child has little control. At this stage, the child learns how to look after others’ needs and, during this process, begins to suppress their own. The more the child fulfils this role, the more skilled she* becomes at suppressing her own needs.

*(‘She’ because, in the patriarchal society within which we live, men hold more power than women, and are therefore taught to have more of a voice and act out their feelings. In contrast, women tend to internalise their feelings and act in. This is why there are so many more women in mental institutions as opposed to prisons).

How to move forward

Most women have real difficulty in consciously acknowledging the anger they hold surrounding their roles as children, as this would mean recognising their own resentment toward their parents, particularly their mother, whom they had always tried to protect against any emotion perceived as negative.

For the guilty child who finds themselves, a decade later, stating that ‘it wasn’t that bad’, it’s important to remember that emotional hunger isn’t always about receiving nothing. It can also be about receiving the wrong thing (for example, being given gifts and money when what you really need is a hug).

Alas, there doesn’t need to be any hatred aimed towards anyone, only awareness, and this is what recovery strives for.

Recovery relies on evoking an awareness of impulses, feelings, and needs that originate within oneself. The purpose of this is to encourage greater autonomy and self-directed identity, where what one has to say is listened to and made the object of exploration. This is to combat the issues with self-image that many people with Anorexia experience (very poor with extremely high ego-ideal* standards).

*(The ego ideal is a core component of the superego in Freudian psychoanalytic theory, representing the internal image of the ‘perfect’ self that an individual strives to become).

I needed to express myself, not only so that others might hear me, but so that I could hear myself.

And this leads me onto my next point…

The importance of art in recovery.

Art acts as a vital link between the anorexic and the outside world. While both are about expressing oneself without words, unlike anorexia, which acts like a numbing agent where being constantly fearful of a lack of control can translate to a total cutting out of emotions, art helps and guides one back to communicate with others, bringing pain into the open. It does this owing to the separation that it offers.

Art can help one to distance their emotions from themselves. Therefore, instead of feeling guilty for feeling a certain way, as they might previously have done, getting their emotions down on paper can help them to analyse their feelings as though they were observing someone else.

No longer did I feel guilty about wasting so much time in hospital, because I was now using the experience to fuel my work.

Mindfully honouring creativity helps one transcend the feeling of deficient emptiness that drives self-destructive behaviour. ‘What is in must out.’

Ultimately, though, recovery can only be achieved when one can see the emptiness of their behaviour. Anorexia is not good, not evil, just an outside ‘thing’ that has been unintelligently used to ease suffering. I write ‘unintelligently’ here, not to be rude, but because no addiction in the history of the world has ever alleviated more suffering than it has ended up causing.

Art, however…

Art saves lives.

-

The True Meaning of Christmas: Presence Over Presents

Christmas isn’t about having the most presents; it’s about having the most presence.

It’s about spending quality time with your loved ones.

It’s about gift giving, not just for the sake of it, but to show gratitude and appreciation for the people who matter most in your life.

‘I saw this and thought of you’ vs ‘I saw this and thought, that’ll do.’

It’s about using the season to reflect and reevaluate your values in life, knowing that the only way to achieve the life you desire is to get comfortable asking the big questions that might lead you to somewhat uncomfortable answers…

What do I want to carry forward into 2026, and what do I want to leave behind?

Only when you’re prepared to let go of the beliefs that you hold surrounding happiness: that it can be bought, and that your purpose in life is to consume, can you truly achieve the life that you deserve.

-

Modern Slavery in the UK’s Car Wash Industry

In every community in the UK, people are being exploited for cheap labour as part of modern-day slavery. The hand car wash sector is especially affected by this, as research by the Modern Slavery Helpline highlights.

27% of cases recorded to the helpline about labour exploitation concerned car wash workers.

Despite this, in 2019, the government rejected a call for a trial licensing scheme to try to tackle the issue. If approved, this would’ve ensured that all carwashes were complying with employment, tax, health, safety, and environmental laws. Because it wasn’t approved, however, the exploitation continues.

How is it allowed to continue?!

The chair of The Car Wash Association (CWA), Brian Madderson, expressed his disappointment with the outcome of the calls for a trial licensing scheme in an interview with BBC News.

We are being given words of reassurance, but what we need is firm action against the modern slave owners who evade taxes and exploit vulnerable workers.

And that they do…

What are they trying to hide?

In 2022, Nottingham Trent University partnered up with the government-backed Responsible Car Wash Scheme (RCWS) and the Home Office’s modern slavery prevention fund.

After conducting surprise inspections of carwashes in Leicester, Suffolk and Norfolk, they found that only 7% had undertaken right-to-work checks, 6% had written contracts with workers, and 11% handed out payslips so that they could prove they were paying the legal minimum wage.

What’s more, less than half of carwashes (41%) were registered companies, indicating that most are not registered with the tax authorities at all.

And so, this begs the question (again)…

What are they trying to hide?

There are an estimated 5000 hand car washes in the UK, employing at least 15,000 people, yet more than 90% of them are employing workers illegally…

Unfortunately, exploitation in the car wash industry is widespread (see above). Inspections may have only been conducted in three places as part of this research, but as Teresa Sayers, the managing director of the RCWS, says:

The study was representative of the picture across the UK.

Evidently, it’s an endemic, and one which is highlighted by The Salvation Army.

Just consider the story of Karel, for example…

Karel, who is in his early twenties, used to live with his family in Poland. However, a lack of job opportunities in his hometown made him keen to pursue a different life. He was therefore interested when he heard of work opportunities in the UK. He signed up in Poland, and arrangements were made to bring him into the UK by coach.

When he arrived, however, the opportunities that he had been promised turned out to be working in car washes, where the conditions were awful, and so was the pay. But Karel was stuck… Whenever he spoke to his traffickers about how badly he was being treated, they responded by threatening to kick him out onto the streets with no money, no ID documents and nowhere to stay. They even made threats of violence against him and his family back in Poland, claiming they knew his home address and would hurt his relatives if he didn’t comply. They also showed him a collection of weapons that they said they would use on anyone who went against them.

After eight months, Karel eventually found the courage to run away and went to the police. He was referred to The Salvation Army for support. There, specialist staff assessed his situation and planned for him to be transported to a safe place, away from the area his traffickers were operating in. He was looked after in a safehouse for several months until he decided to return to Poland to be with his mother.

Like Karel, vulnerable people all around the world are being promised a better life in the UK, only to get here to find that they have been duped.

Life isn’t better for them here, as I realised today while I was waiting for my car to be valeted at a local carwash…

My experience

The workers had a system going from entry to exit. Working their way down the long line of cars, each was a component in the machine. Most wore only t-shirts. How they could do it, I have no idea. I was sitting inside my car with the heating on, and even I felt cold, so they must have been freezing.

I felt a sense of unease the whole time I was there. Not because the men did anything to make me feel uncomfortable (they all seemed lovely), but because I felt like, by taking my car to them, I was being an active participant in their exploitation.

How is it fair that I get to sit in my Audi while they have to scrub my car for a pittance just to be able to feed their families this Christmas? It’s not fair. And the same idiots who take to Facebook to voice their grievances about immigration are with me in the queue.

If people are so concerned about immigrants ‘taking our jobs,’ then why aren’t they washing their own cars?…

I don’t know if the carwash I visited was exploiting their workers or not — I paid using my card, so from a monetary perspective, things did seem above board, but still, I felt so sorry for the workers.

Is this really the Britain they imagined?

I left the guy cleaning my car with a £20 tip at the end, and I myself with a lingering sense of injustice, yet again, at the state of this country.

Where is the better life they were promised?

Where is the justice?

-

How To Break Free From Societal Norms and Embrace Authenticity

From what food we eat to who we date, we are told to be self-restrained in all areas of our lives.

Don’t eat the cake, you’ll get fat.

Don’t date the girl, you’ll go to hell.Women are shamed into shrinking themselves, going to excessive lengths to reduce every aspect of their body, their personality, their life. This is because, as a society, we are taught that it’s somehow ‘wrong’ to take up space.

Consider giants, for example. Representing the human body, but magnified, a giant is essentially evil cosplaying human. Their portrayal in folklore highlights how people are taught to fear themselves — or, more specifically, their size.

How to make a giant: Take the human body and enlarge it to the point of being monstrous, and voila, you have created the next villain.

Ever wondered why the beauty industry and the market for diet products is so large? It’s precisely because of the fear that is instilled in us all regarding our size.

By creating problem areas for us to feel insecure about, they can sell us the proposed cure…

If we’re not too much, we’re not enough. Why can’t we ever just be ‘right?’

Women who flaunt their sexuality are ‘sluts’, ‘whores’, and ‘slags’. Women who don’t are ‘prudish’ and ‘frigid’.

If you’re a virgin, ‘what are you waiting for?’ If you’re not, ‘why didn’t you save yourself?’

It’s an extremely immoral marketing strategy, albeit an, unfortunately, all too successful one…

Alas, a lie of happiness packaged up in pretty packaging is still a lie.

As people are shamed for not having the ‘right’ body type, so too are people shamed for not dating the ‘right’ gender.

Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind.

The quote above is used, not because homosexuality is an ‘abomination’ to the natural order, as the bible would have us believe, but because it violates the neat categorisation of men from women, something which homophobes just can’t fathom.

Being so backwards-thinking in their ways, homophobes can’t fathom the dynamics of same-sex relationships.

Who is the man, and who is the woman? Where does that differentiation come in? How can a same-sex couple have children?

A lesson in biology might help if their confusion was genuine, but the reality is that they aren’t confused; they’re just angry. They’re angry that people would dare to go against the norms of society in such an overt way. And maybe they’re jealous, too. They would never admit it, of course, it might shrink that colossal ego of theirs, but maybe, just maybe, they’re jealous that a relationship can actually be founded on love, real love (who would’ve thought it!), not just a need to procreate.

The fact is that whether it be homophobia, fatphobia, transphobia, or xenophobia, all forms of oppression have five unassuming letters in common… p-h-o-b-i-a.

Phobia (noun): An extreme or irrational fear of or aversion to something.

What are the bigots scared of?

In a system that places money and capitalism on a pedestal above all else, a happy society is a dangerous one, for a happy person doesn’t feel the need to spend money to feel better. This is why all the things we do in life that bring us happiness are, in some way or another, deemed to be ‘wrong.’

But… It doesn’t have to be this way. When the oppressor retains their power by exuding as much hate as possible, we can all work together to erode tyranny by the power which they cannot know — the power of love.

Eating what you want to eat because you love food, not eating what you think you should eat because some shitty commercial you saw on TV last night told you chocolate makes you fat.

Loving who you want to love because you have found the person you want to spend the rest of your life with, not loving who you think you should love because you can still remember your mum telling you, when you were ten, that her ‘only wish for you in life is to meet a nice man like your dad who will look after you.’

Spending your days doing work that you want to do, not doing work that you think you should do because a career advisor told you in high school that ‘creative careers don’t pay.’

Stripping back the layers to realise that you don’t need to keep buying into someone else’s narrow-minded vision of a ‘perfect’ world, because, as some of us have learned the hard way, perfection doesn’t exist.

You, however, do, and this is your life, so do with it as you please.

-

The Interplay of Art and Religion: A Historical Perspective

Religion has been depicted in art for millennia, taking off most notably during the Renaissance period, dated between the 14th to 17th centuries.

In a bid to transition away from the Middle Ages and foster a renewal of Christian thought, the Renaissance period saw religious themes becoming deeply embedded in art and architecture. Many religious figureheads began to commission famous artists to paint murals for their establishments as part of this move to modernity. This is how one of the most famous pieces of artwork of all time, The Last Supper, came to be.

The Last Supper (see above) was commissioned by Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, who wanted to include the mural as part of a larger renovation of the Santa Maria Delle Grazie monastery. Similarly, The Creation of Adam was also commissioned, though this time by Pope Julius II, who wanted to use it to cover the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.

Why were religious figureheads so eager to commission artists to create for them?

Because the themes of religion are rooted in concepts that are difficult to put into words, art offers a unique language, using symbolism, iconography, and aesthetics, to explain the unexplainable. This is why, upon combining art and religion, the results are so breathtaking.

While there have been many examples of art being used to promote religion, as in the case of The Last Supper and the Creation of Adam, there have also been many pieces of ‘religious’ art made in satirical ways as a means to question its authority.

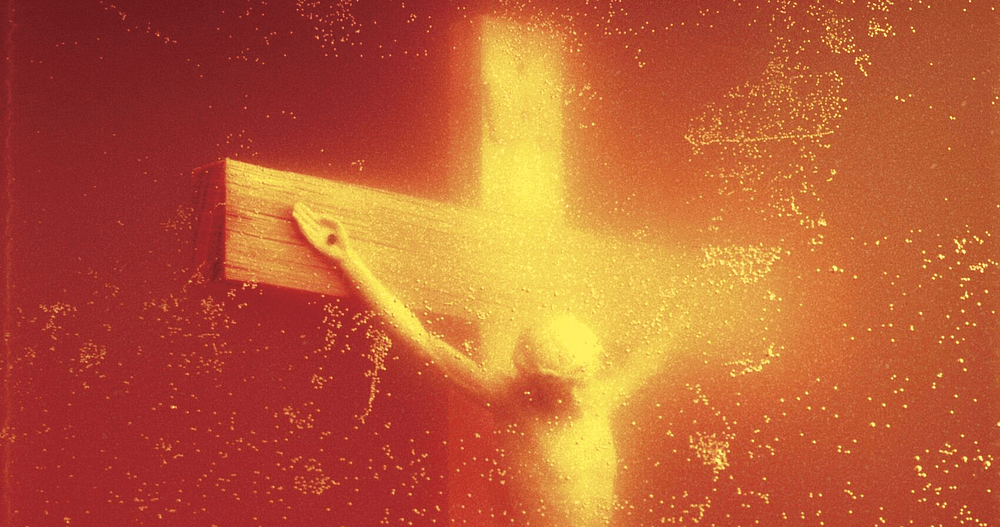

One artist who sought to encourage people to reimagine religion was the American photographer, Robert Mapplethorpe (1946 – 1989).

Having been brought up catholic, despite no longer being religious, Christian imagery inspired much of Mapplethorpe’s work. Religious themes of punishment and transcendence were commonplace in many of his well-known photographs, particularly those involving homoerotic or sadomasochistic themes. Creating a delicate balance between the painful and ecstatic, Mapplethorpe often framed his images in a way that suggested a struggle between these two concepts.

Another artist who has reframed what most people consider ‘religious art’ is the American photographer and visual artist, Andres Serrano.

Like Mapplethorpe, Serrano uses religious imagery in his work, something which has similarly earned him a reputation as being controversial.

Serrano’s most famous piece, Piss Christ (see image below), was created in 1987. Its creation saw Serrano putting a plastic crucifix into a glass of his own urine.

Well aware of the Catholic obsession with the body (that of Christ and those of sinners), Serrano sought to confront the discomfort most people feel with their own bodies and their products, and the prevailing cultural disgust for bodily fluids.

Over the years, many people have found Serrano’s art offensive. In 2011, French Catholic fundamentalists attacked and destroyed Piss Christ with hammers as part of an ‘anti-blasphemy’ campaign. Serrano’s photograph of a meditating nun was also damaged in the attack. What the attackers failed to understand, however, was that Serrano himself is a practicing catholic. Piss Christ, therefore, wasn’t created to undermine religion, but rather, to do the opposite – to take a stance against the misuse of religion and criticise the commercialisation of sacred imagery.

Crucifixion is a very ugly and painful way to die, but we see the crucifix as a very aestheticized object which has lost its meaning.

In a sense, then, Piss Christ is simply Serrano’s way of returning the story of Jesus back to something like its physical reality.

What is evident from my research is that artists at large find great influence in religion. Roughly one-third of the paintings in the National Gallery’s collection of Western European art are of religious subjects. Furthermore, using myself as an example, I am not religious, yet my poetry often touches upon themes of religion.

To quote Andres Serrano, the photographer behind ‘Piss Christ’:

For me, art is a moral and spiritual obligation that cuts across all manner of pretence and speaks directly to the soul.

Serrano’s belief is in line with Buddhist philosophy, too, which suggests that the imagination involved in the process of creating or looking at art, or listening to music, is a type of meditation, and, in turn, a very important part of the journey towards enlightenment.

What do art and religion have in common that has made them such a fitting pairing throughout the years?

There’s a reason why cathedrals are adorned with art, commissioned murals covering ceilings and walls, as there’s a reason why hymns are sung during service, and poetry is read, and it’s because art has the unparalleled capacity to create a sense of unity and shared experience within us all.

This is why, throughout history, art and religion have remained so deeply intertwined. From the Renaissance period to the twenty-first century, religion continues to be referenced in art and music, this being a trend that is showing no sign of stopping any time soon!

Worshippers turn to the church for answers; artists turn to the canvas.

As the West becomes increasingly secular, we are seeing more art that questions religion and its place in society. In turn, we are increasingly being encouraged to grapple with themes that explore the fundamental aspects of the human experience and the nature of existence.

Whether it be in the stroke of a paintbrush or the reciting of a bible passage, ultimately, the purpose of both art and religion is to answer the questions the world didn’t even know it needed answers for.

-

The Reversal of LGBTQ+ Rights in the Age of the Far Right

In Italy today, if you have a child through non-traditional means, you can face prison time. This move is part of Giorgia Meloni’s agenda — Italy’s first female prime minister and leader of the most right-wing government since World War II, the Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia).

‘Yes to the natural family, no to the LGBT lobby,’ Meloni declared in a recent interview. ‘Children should only be raised by a man and a woman.’

These outdated beliefs have real and devastating consequences. In 2017, the city of Padua in Northern Italy began cancelling birth certificates issued to the children of same-sex couples. With the removal of non-biological parents came the removal of their rights. As one lesbian mother explained:

I won’t be able to take my daughter to school, make medical decisions for her, or travel abroad without her biological mother’s written permission. And if her biological mother were to die, my daughter would be declared an orphan and could be adopted.

It would be easy to read this, as a lesbian, and think, “That won’t affect me.” But as history has proven time and again, an attack on one marginalised group is an attack on all marginalised groups.

The United States: Threats to Marriage Equality

Next week, on November 7th, the U.S. Supreme Court will decide whether to hear a case brought by former Kentucky county clerk Kim Davis, seeking to overturn the landmark Obergefell v. Hodges ruling — the very case that guaranteed nationwide same-sex marriage rights in the United States.

Hillary Clinton warned about this back in August: “The Supreme Court might do to gay marriage what they did to abortion,” she said, urging “anybody in a committed relationship out there in the LGBTQ community to consider getting married before the nation’s highest court takes that right away.”

Whether the case is ultimately heard or not is almost beside the point; the fact that it has reached this stage is what matters. How, a decade after gay marriage was legalised in the U.S., are we seriously debating whether it should be revoked? The fact that it’s 2025 and we’re still arguing over whether love should be legal is nothing short of absurd.

The United Kingdom: Farage and the Normalisation of Prejudice

Closer to home, Reform UK leader Nigel Farage recently reignited debate over LGBTQ+ rights in Britain by declaring that legalising same-sex marriage was “wrong” during a live phone-in on LBC. Farage’s remarks come at a time when Reform UK is polling strongly ahead of the next general election, already controlling ten councils across England.

Like Meloni and Davis, Farage disguises prejudice as “concern” for children. Despite being twice divorced himself, he insists that “the most stable relationships are between men and women.” One can’t help but wonder whether figures like these have ever truly interacted with same-sex couples — or whether their hate blinds them to love itself.

Whatever their personal motives, far-right leaders share a common strategy: control through division. They frame their attacks on LGBTQ+ people as moral crusades against “woke ideology,” using scapegoats to distract from the real problems — inequality, economic decay, and systemic failures.

The problem is not with immigrants, or trans people, or gay people, or women. The problem lies with the system — and the conservative values that sustain it.

At the root of these values are money and religion: two forces that have long dictated what is considered “moral.” The U.S., where LGBTQ+ rights are again under threat, has the largest Christian population in the world. Similarly, Italy, another nation rolling back rights, remains overwhelmingly Catholic — with about 75–80% of its population identifying as such. The Catholic Church deems homosexual acts “intrinsically immoral” and “contrary to natural law,” defining morality strictly within the confines of a heterosexual marriage.

Religious teachings like these are designed to instil fear and discourage defiance. Even Pope Francis, often praised for his progressive tone, draws a sharp distinction between orientation and action: being gay, he says, is not sinful — acting on it is. This distinction reveals the core of the issue: control. As long as queer people remain invisible, celibate, and compliant, they are tolerated. The moment they live authentically, they become a threat.

The Family: The Frontline of Ideological Control

And where is that control most easily exerted? Within the family. The family is the first and most intimate social institution — the place where children absorb the values, norms, and beliefs that shape their worldview. From an early age, girls are handed dolls to nurture, while boys are given toy guns to dominate. These small acts of socialisation uphold patriarchal norms that ripple through generations.

Homosexuality threatens this structure. Two same-sex parents challenge gender stereotypes and blur the rigid roles that sustain the patriarchy. For conservatives, that’s terrifying. If people begin to question one traditional value — the “natural” family — what’s to stop them from questioning others?

That’s why nontraditional families, whether queer or blended, are viewed with suspicion. They symbolise freedom from the “cereal packet” model: the breadwinner father, stay-at-home mother, and two obedient children. For the far right, such freedom is dangerous — because it erodes the foundation of their control.

So why are LGBTQ+ rights reversing? Because the far right thrives on fear, obedience, and nostalgia for an imagined past. And as education, diversity, and liberalism rise, their grip on power weakens — prompting them to double down.

A recent YouGov survey on the 2024 general election revealed that Reform UK performed significantly better among those with lower levels of education — 23% of the vote — compared to just 8% among those with higher education. The opposite is true for progressive parties like the Greens.

Make of that what you will. But if history has taught us anything, it’s that blind compliance never leads to progress.

-

From Domesday to Paycheck: The Story of Money and Power

For centuries, people have been sold the lie that to live is to work. It’s why, when meeting someone for the first time, one of the first questions we ask is, ‘So, what do you do?’

Our jobs have become our identities.

It’s tempting to believe that this obsession with work is modern — a product of capitalism and right-wing politics — but in truth, it’s a mindset that’s been with us since the Middle Ages.

Just look at our surnames for proof.

From Names to Chains

When surnames became common in 12th-century Europe, people were often identified by their trade. A blacksmith named John became John Smith. A man who milled grain was Miller. Barker meant shepherd, Carter a deliveryman, Chandler a candlemaker, Cooper a barrel maker, Fisher a fisherman.

Our very names became our jobs.

This wasn’t a coincidence — it was by design. The rise of surnames followed the Norman Conquest, part of a broader system that bound ordinary people to their labour and reinforced social hierarchies.

Power, Land, and Control

The Norman Conquest wasn’t just a battle — it was a complete social reordering. The Anglo-Saxon aristocracy was wiped out, their lands seized and handed to Norman lords. From this power grab, feudalism took root: a system in which land was exchanged for personal service.

Most of the population became landless peasants — serfs — obliged to work for their lords in exchange for “protection.” Bound to the land, they were little more than property.

And, once again, surnames reinforced this system. If your name was Smith, you were a blacksmith — and you’d likely stay one. Mobility was near impossible.

To document and control this structure, William the Conqueror commissioned the Domesday Book, a vast record of who owned what. Ostensibly a survey of wealth, it was, in reality, a tool of surveillance and taxation — an early example of government using information to consolidate power.

The names in it tell their own story: those recorded were landowners, not labourers. The working class — those who built the kingdom — were invisible.

The Norman Legacy Lives On

Fast forward nearly a thousand years, and little has changed. Today, around 70% of land in England is owned by just 10% of people, many of whom are descendants of those same Norman families.

Take the Grosvenor family, led by the Duke of Westminster, for example. The duke descended from William the Conqueror’s master huntsman, Hugh le Grand Veneur. Asked about his success, the late Duke once remarked that it “helped to arrive with William the Conqueror.”

Indeed.

The Conquest didn’t just reshape class — it entrenched patriarchy too. Women who inherited land could only keep it if they married a Norman. Those who didn’t lost everything.

Nearly a millennium later, echoes of that system persist. Women still face inequality, workers are still undervalued, and society continues to function as if people exist merely to fund someone else’s dream.

It’s 2025, but we’re still working the land for those who own it.

The Industrial Age: Old Hierarchies, New Names

Workers’ rights took centuries to develop. The first union — the General Union of Trades — wasn’t founded until 1818. Yet even as unions rose, the cultural script remained the same: work hard, stay in line, and don’t question the system.

It wasn’t until 1926 that the nine-to-five work schedule that so many of us live by today came into public consciousness. It wasn’t born from compassion, however, but rather, control.

In 1926, Henry Ford introduced a 40-hour, five-day workweek — seemingly progressive, but deeply self-serving. Ford’s capitalist ideals aligned disturbingly close to fascism. As Hitler himself said, Ford was “the leader of US Fascism.” His model disguised exploitation as benevolence — and we still live under it.

Money: The Modern Feudal System

Even when companies like Kellogg experimented with shorter hours in the 1930s, workers eventually chose longer days for more pay. Time — the most valuable thing we have — was traded for money, a man-made construct that continues to rule us.

We aren’t in Norman England anymore, but we’re still serfs — only now our lords wear suits.

Money has become what land once was: the ultimate instrument of control. Where medieval peasants were tied to soil, modern workers are tied to wages. Those without money starve, while the elite accumulate wealth they could never spend.

The exchange system that once sustained communities has been hijacked to sustain hierarchies. Through money, states maintain order, extract taxes, and reinforce class divisions.

Money (noun): ‘The most disastrous failed experiment in the history of the world by far. ‘Love me, and only me’, it silently screams.‘

Is There Another Way?

In the Stone Age, people lived through exchange, not exploitation. Depending on their occupation, a tribe could exchange livestock, fish, wild game, and later, with agriculture developing, grain. They bartered what they had, ensuring that everyone could afford what they needed. No one was homeless. No one starved.

If people didn’t have a cow to pay for something back then, they could exchange what they did have — shells or beads were common — to buy it instead. If people don’t have money to pay for something today, however, then they simply won’t buy it. This is why millions of people around the world are at risk of famine, and hundreds of millions are on the streets, homeless, all the while the top 1% are living it up in their mansions.

If we stripped away profit-driven production and built societies that prioritised need over greed, we could create communities based on contribution and compassion — not competition.

People already create and give out of love every day — artists, volunteers, caregivers. Imagine if that were the norm, not the exception.

Despite common arguments that greed is human nature, ‘we are animals, and there will always be a ruler’, there is a stark difference between us and the rest of the animal kingdom. Unlike every other species on Earth, humans have an advanced capacity for complex moral reasoning.

‘The Lord of the Flies begs to differ,’ I’ve heard people use as a counterargument. ‘Without a hierarchy, the world would descend into savagery’, they continue, all the while forgetting that The Lord of the Flies is FICTION. There is no truth to it.

The fact is that while humans have the capacity for evil, they also have a capacity for good, as real-life examples prove.

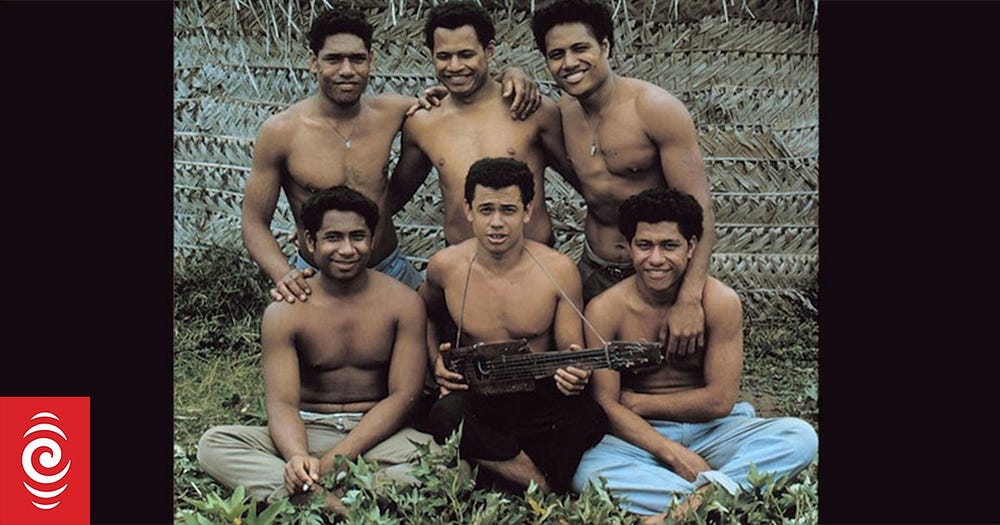

Unlike The Lord of the Flies, which is a fictional novel, The Tonga castaways’ story is a real story about six teenage boys (pictured above) who ran away from boarding school in 1965, stole a boat, and were shipwrecked on the uninhabited island of ʻAta. They survived for 15 months by forming a cooperative community, building a shelter, and maintaining a sustainable food source, all before being discovered and rescued by Australian fisherman Peter Warner in September 1966. Their story is often contrasted with Lord of the Flies because, unlike the fictional account, they worked together rather than descending into chaos, proving that cooperation, rather than savagery, can be the dominant response when societies collapse. How so? Because we are not animals bound by instinct, we are human beings capable of moral choice. We therefore do not need to act on impulse to make selfish decisions that benefit only ourselves.

Our greed is not innate — it’s learned. And just as it was learned, it can be unlearned.

If we could only let go of our fear and selfishness and simply — give — this world could be beautiful again.

-

Redefining Health Beyond Numbers

I first became aware of my body, in a pinching and prodding way, just over a decade ago. I can remember standing in front of a mirror and scrutinising my stomach, while feeling a sense of shame that I didn’t have the ‘definition’ that the women I saw online had.

I was 14.

From that day forward, I vowed that I would change, and that I did.

My dad has always been a runner, and I decided to follow suit. I bought the cheapest running shoes they had in Sports Direct, a pair of Karrimor’s, and off I went. All it took was one decision to change the course of my life for the next decade.

After a few weeks of running with my dad, I decided to join my local athletics club. I started entering races and, ever the perfectionist, researched how I could get faster.

I landed at the conclusion that to get faster, I had to run more and eat less.

I cut out all saturated fat, sugar, and simple carbs from my diet. At my worst (or, as I would define it then, my ‘best’), I was eating only fruit and vegetables, and running 50+ miles a week, all the while I was still growing.

My bones became so weak that I developed a stress fracture in my foot, and still I ran. I was later diagnosed with osteopenia, the early onset of osteoporosis. At the age of 15, I had the bone health of an 80-year-old, I was told.

I was referred to CAMHS, the children and adolescents’ mental health services, and diagnosed with Anorexia Nervosa.

The rest is a blur of hospital appointments, training sessions at the running track, yelling matches with my parents, discussions (that went nowhere) with my dietician, blood tests and, finally, a section.

It was two weeks before my seventeenth birthday, I was soon to be entering the final year of my A-levels, and I was finally winning the races that I had been training so hard for. On the outside, with the exception of my emaciated body, everything looked like it was going well for me… Yet I was being forced to go to the hospital to receive treatment for an illness that I didn’t even think I had.

‘I’m just disciplined,’ I told myself and everyone else, all the while ignoring the ache in my chest. Alas, I wasn’t disciplined, I was dying, I now realise.

When I was first admitted to the hospital, it was hard. So hard. I felt like I was in a period of grief, almost. Not being able to run and being forced to eat all the foods that I had refused to eat for so long was terrifying. It felt like all the control that I had spent so long striving to have was suddenly taken away from me, and I was scared of what would happen to my body.

For the first few weeks of my admission, I wasn’t even allowed to go for a walk. Had I not been sectioned, there is no way that I would’ve stayed in there, but as I was, I wasn’t able to leave. I had to sit with the discomfort.

I was placed in an anti-ligature room because I couldn’t be trusted not to kill myself. I had to be supervised while I went to the toilet because ‘the exertion could be dangerous’ (it would be laughable if it weren’t true). I vowed that as soon as I could leave, I would.

Fast-forward two months, and following a review with my psychiatrist, my section was lifted. I was informed of my rights — as I was no longer sectioned, I was under no obligation to stay — but to everyone’s surprise, I did.

I stayed.

I was still very fixated on exercise, and the team knew that upon my return home, I would go back to running, so to ensure that I could return to it in a more gradual way, I was allowed to go to the running track when I was on home leave. It was a good feeling. The thing that had kept me going throughout my hospital admission was finally within reach again.

All I could think about was getting home to return to running, but I was more responsive to therapy and, for the first time, able to admit that I was ill and did need help.

I stayed in the hospital for a further four months until, finally, on the 1st of February 2019, after a six-month admission, I was discharged.

Keen to progress with my running, I started racing again after a couple of months. I soon discovered, however, that I couldn’t get back to the level I was at prior to being hospitalised without sacrificing the recovery that I had spent so long working towards.

I felt disheartened, and it wasn’t long until I started to experience the all too familiar sense of dread upon waking up and realising that it was time to go running. This time, though, instead of reverting to food restriction, as I had done before in an effort to ‘get quicker’, I made the decision to stop running altogether, and, in its place, started working out at home. It still wasn’t healthy, though, because I didn’t enjoy it.

Until just two weeks ago, I was still forcing myself to exercise five days a week. But not anymore. Life’s too short to spend it feeling guilty for missing a workout. I don’t want my worth to be tied to movement anymore.

The fact is that if you feel like something awful will happen if you don’t exercise, you don’t have a healthy relationship with it, as I learnt the hard way…

When I was running every day, I hated the reflection that I saw in the mirror. Everyone told me how ill I was, how thin I was, and the weighing scales proved that I was incredibly poorly indeed, but for some reason, when I looked in the mirror, I couldn’t see reality. Instead, I saw someone whose size was ‘above average’, and this is what made it so hard for me to recover, and why I was ultimately sectioned, because…

Why do I need to gain weight when I’m already too big?

My brain was gaslighting my body, big time.

The main thing that stopped me from wanting to recover, when I did come to terms with the fact that I was ill, was the anxiety that I had surrounding what would happen to my body if I stopped exercising. I thought that gaining weight was equivalent to losing control. But, in a weird turn of events, I feel better now than I ever have, and that all comes down to ignoring the rhetoric that is pushed on us all by the media.

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ remedy when it comes to health. What is healthy for you might not be healthy for me.

Since I stopped exercising in such a structured way, I have felt more comfortable and at peace with my body than I have in over a decade.

I walk my dogs every morning, and I go hiking with my dad once a week, but I do these things because I love them. When I’m out in nature, I’m able to, albeit somewhat contradictorily, find myself in the act of getting lost in something bigger than myself. The worries I have about the way the fat on my stomach rolls, or the way my thighs meet, evaporate when I am standing atop a mountain, listening to the sound of flowing water cascading down a nearby waterfall, or watching a flock of birds take flight as they embark upon their great migration for the winter.

When I was sitting in the back of an ambulance on my way to the hospital, aged 16, I never would’ve believed that there would come a time when I wouldn’t need to exercise to feel ‘enough.’ But I am here, finally, and it feels amazing.

It’s taken a lot to get here, and I don’t know exactly what the turning point was, but I can say with certainty that being with my partner has been a game-changer for my recovery.

My partner, Lucy, loves and accepts all of me, and that helps me to love and accept the parts of myself that I have always had such a hard time with. She shows me that I don’t need to burn myself into the ground in order to be worthy of love. I am worthy of love simply because I am alive.

Scrap BMI, to determine your healthy weight, hold out for the moment that you stop obsessing about your body. Whatever your body looks like in that moment is representative of true health.

I know it’s not what you want to hear, but you could have the body of a Victoria’s Secret model, but if all you’re thinking about is food and exercise, then you’re just as unhealthy as someone who is morbidly obese…

I’m not saying that I will never exercise in a structured way again, because I might, and should I want to, in a healthy way, I will hold space for doing so in the future, but right now, I have things that are of greater importance to me than controlling my body.

Art and love over food restriction and exercise. Hope over control… I have finally tasted contentment, and oh, how sweet it is. ❤

-

How To Find Your Purpose In Life

Your soul aged three is the same as your soul aged six is the same as your soul aged twenty-three and ninety-six.

For while your body changes, grows, and fractures, with each new skin cell

forming untouched life, your soul — underneath, above, within — remains the same.What you loved then, given a chance, you will love now.

Creating for the sake of creating, for the love, not the accolades, you must slow down enough to get back in touch with your soul, and, in turn, all the things that lit you up as a child.

It’s so easy, in a society that places money on a pedestal, to get caught up in the rat race, but what will bring you true fulfilment in life isn’t something that can be chased and ‘won’, for it is already within you.

So, next time you’re struggling to find your purpose in life, remember that perhaps the reason why is that you already have it.

Your purpose is not something that can be found, so much as it’s something that can be rediscovered.